Atomic Habits

Summary

Atomic Habits by James Clear is about changing habits or developing new ones. It proposes a framework consisting of 4 laws that can be used to achieve significant changes in our lives. The book includes anecdotes from various fields such as sports and business. The goal is to find simple and easy things that lead to a huge impact once they accumulate. The book is described as a manual/framework for applying changes to our lives to harness transformative changes.

Habits

A habit is something that is done over and over, usually automatically. Some habits are good, while others are not so good.

Clear started a blog out of his habit of writing, which eventually led him to a thousand subscribers. This reminds me of the book Show your Work, where we should share our work instead of marketing ourselves, and eventually, people will find us.

Dave Brailsford is a cycling coach who was hired and changed the history of the British cycling team. The British team had never won the Tour de France in 110 years, the most important event in the category. With the changes proposed by Brailsford from 2007 to 2017, the team won 178 world championships, 6 Olympic medals, and 5 Tour de France titles, considered the most successful run in cycling history. What he did was break down every single aspect of cycling and look to improve each by 1%. When all those changes were put in place, it resulted in a phenomenal change.

There is a statistic, which I have no clue how to calculate, that if you improve by 1% every day, by the end of the year, you are 37 times better than when you started. This reminds me of Art & Fear, how each work informs what needs to be worked on in the next piece.

The Enemy

The problem with habits is that they are hard, and improvements take time to manifest. To intellectually prove this, consider that if a plane leaves the LAX airport and adjusts the course by only 3.5%, it will land in Washington, D.C. instead of New York.

The goal is to make small changes that will lead to different behavior. Everyone wants to achieve something, but in order to get there, it is required to make adjustments as we go; therefore, the journey is what matters, and the result is just a consequence.

A parallel with compound interest is drawn, where the outcome is the result of compound interest, which could be positive or negative. Everything can benefit from that. The more you help people, the more you can find people willing to help you. On the other side of the spectrum, if you constantly have negative thoughts about yourself, it is likely that you see life and things that happen to you through the same lenses.

There was one day that I attended a dance party. My first 4 dances were horrible, and the fact that I had just started dancing about 2 months prior destroyed my confidence. That night I did not dance with other people.

Results

We all want the result, but we don't commit to the changes. People make a change and fail to keep doing it because no result or progress is evident. There is no workaround; we need to stick to the changes until the result finally becomes visible. This is called the Plateau of Latent Potential.

The funny thing is people never realize the effort you put towards something, but when the change happens, they see it as an overnight change. That is one of the reasons I believe people underappreciate the artist; they don't see the process behind it.

System

What we want to achieve is our goal, but it won't happen without meaningful and intentional actions; that is the process, and it should be our focus. Think about the goal as the direction you have to take, your end goal, your destination. The process is the actions you take to get there. What way should you take to get where you want?

The reason people fail to achieve their goal is that the process is not working properly. It requires analysis and alterations as we go. The mentality should be about what we can do now, rather than what we want to achieve. Our commitment to the process will decide the end result.

That reminds me again of Art & Fear, where it mentions that as soon as the artist strokes the canvas for the first time, it will decide how it will look in the end. That is because it is a chain reaction. The first stroke will lead to the next one, limited by the current one.

Identity

In order to make changes, we need to focus on what needs to be changed and how to change them. For that, there are 3 layers:

- Outcome: this is what you get out of it.

- Process: this is what you do.

- Identity: this is what you believe.

Many times people struggle to make changes because they are solely based on the outcome they want to achieve. That can be a daunting task. What Clear proposes is that we should make changes based on identity. It is about who you are and who you want to be. In the book, he mentioned a person offering a cigarette to someone. They can answer: "I quit," or "I am not a smoker." This is a change in their identity; if I am not a smoker, there is no reason to accept a cigarette, however, if I quit, you may fall short.

Everything we do has a belief behind it, and most of the time, we are not really aware of it. The goal is to identify that and change it. That also includes bad habits; what is the second gain of our bad habits?

People will always be motivated to do things that bring them pride. So when people start to make changes, they fall short because it is not connected to their identity. We can always change our goals into an identity:

- I want to read more → I want to be a reader.

- I want to write more → I want to become a writer.

- I want to exercise more → I want to live healthier.

The beliefs we have are also hindering our abilities to move forward. How many people do you know say:

- I am terrible at names.

- I am terrible at directions.

Those are beliefs that can be changed, but the person sees themselves as that, so it will be almost impossible to change them because THEY ARE terrible at X.

Changes are hard because they confront our inner values and beliefs; however, if we want to become the best version of ourselves, we need to constantly adjust our identity.

Every time someone forgets somebody's name, they prove to themselves that they are bad at remembering names. That will lead to the identity of being horrible about names. Every time I make art, I reinforce that I am an artist. So, identities are not something rigid and inflexible; they are just an accumulation of "proofs."

When I started coaching trampoline, at the end of one of my classes, my boss asked me what the names of the children that attend it are. I drew a blank and looked stupid for not knowing. Then she asked me to try to remember at least one name per class. Guess what, I started putting effort into remembering their names, and in just a few classes, I had memorized all the names. Despite the good intentions of my boss, I felt that I wasn't doing my best at work, so that prompted me to change ASAP.

Action

Who do you want to be? What do those people do that you can do right now? Once you start doing it over and over, you will become what you want. Once you accumulate small wins, you have proof that you are that thing, and it leads you to have a new identity.

When I visited Tokyo in 2019, I attended a Collage Exhibition called the Miracle of Silence by Toshiko Okanoue. As soon as I got back to my hotel room, I pulled out my iPad and started collaging. A collagist does collage, so I did one. For the next several months, I did collages about any ideas I had. I was not caring about the results; I wanted to do it! I was obsessed with exploring all the possibilities. Eventually, people started to compliment my art, and that made me confident about what I do. For your amusement, here's my first work and the work I consider my best.

Work, 2019, Jonny Garcia

Bler, 2021, Jonny Garcia

Questions to ask yourself:

- What do you want to stand for?

- What are your principles and values?

- Who do you wish to become?

What small steps can you take to reinforce those identities?

Every time you are about to eat something and your goal is to be a healthy person, ask yourself: What would a healthy person do?

Habit formation

When we have no reference about a certain thing, we may do good or bad. Those will be remembered later and will help you decide how to proceed in a similar situation. If it was bad, you will do something differently, but if it was good, you will tend to repeat.

According to behavioral scientist Jason Hreha: “Habits are, simply, reliable solutions to recurring problems in our environment.”

The more familiarity you have with a situation, the more you will automatically respond to it based on your previous encounters. Without actively thinking about it, you are predicting what you should do that will lead to the best outcome possible. Once this decision is automatic, you free up your mental energy, which becomes available for something else. If you have good habits established, your mental energy will be available to focus on whatever you want. In that sense, a habit leads to freedom.

Habits are formed based on 4 simple steps:

- Cue: the trigger that makes you do something.

- Craving: what changes do you want to happen? If you are hungry, you want to feel satisfied;

- Response: this is what you do to change your craving. Once you are hungry, you eat.

- Reward: this is what satisfies your craving. Now you feel full.

Any stimuli we receive can potentially trigger a habit; they need to be interpreted. The craving is what you want to change in the current moment; I want to feel warmer, so you put a jacket on, that is your response, and as you feel better and warmer, you get your reward. Since you learned that putting on a jacket made you feel warmer, this will help you decide what to do in the future when confronted with a similar situation.

When the response requires more energy than you have available or are willing to expend, most likely you will not do anything.

Awareness

Japan implemented a system called Pointing-and-Calling for the train operators, which basically requests someone to say something out loud as they execute. This technique reduces mistakes because it forces people to pay attention to what they are doing. It seems silly, but it reduced mistakes by 85% and accidents by 30%. New York City adopted a similar technique, and the incorrectly berthed subways fell by 57%. The demand to use multiple parts of their body—eyes, mouth, fingers, and ears—increase the chance to notice something wrong. Just like mentioned in the book, when I leave a place, I speak out loud what I need with me: cellphone, wallet, keys, and etc.

That technique reveals that we fail at doing something due to the lack of awareness. So if you want to change something, the first step is to realize what you are doing. As an exercise, the book proposes to make a Habit Scorecard:

- Make a list of your daily habits (p. 64):

- Wake up

- Turn off alarm

- Check my phone

- Go to the bathroom

- Weigh myself

- Take a shower

- Brush my teeth

- Floss my teeth

- Put on deodorant

- Hang up towel to dry

- Get dressed

- Make a cup of tea

- Beside each habit, add a + sign for a positive habit, add - for a negative habit, and = for a neutral habit (p. 65).

- Wake up =

- Turn off alarm =

- Check my phone –

- Go to the bathroom =

- Weigh myself +

- Take a shower +

- Brush my teeth +

- Floss my teeth +

- Put on deodorant +

- Hang up towel to dry =

- Get dressed =

- Make a cup of tea +

To decide which one is good (+), neutral (=), or bad (-), ask yourself: Which ones help you become who you want to be? How are they benefiting you in the long run?

If you are not sure, say out loud what are the consequences of doing a certain behaviour. It will make it more real and easier to identify the bad one.

Making Changes

A research has identified that the more precisely you describe something, the more likely that you will do it. They nominate this process as Implementation Intention. Describe when and how you will do something.

“During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME] in [PLACE].”

Sometimes what is stopping you from starting to do something is a lack of awareness or clarity of how and when to do something. If you have a plan, your chances to do something will be higher.

I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION]

Behavior is like a link in a chain. One thing leads to another. We can use this principle to our advantage. Identify some habits you already do and add something as the next step after it. This is called Habit Stacking.

After I [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT]

This is very similar to hypnotic triggers: When I snap my fingers, you will laugh because it is very funny.

Environment

The environment significantly influences your habits. Depending on where you are, different habits can be triggered. This can be demonstrated via the equation.

Our vision plays a crucial role in our behaviour. In fact, we have about 11 million sensory receptors, and 10 out of those 11 million are dedicated to vision. Visual cues strongly trigger habits. By making something more visible, we enhance the chances of doing it. For example, if you want to drink more water, place a bottle of water in every room. Conversely, if you want to reduce a habit, make the cue invisible. To decrease phone usage, keep it away in another room.

People often think that sticking to good habits and avoiding temptation requires a lot of willpower. However, research proves that individuals with good habits are simply better at avoiding temptation. So, make the good ones visible and hide the temptations.

My good friend Maul once commented on the dynamic change in the house of some relatives. The living room, initially without a television, fostered conversations among people. Once they added a television, people stopped talking and spent more time watching TV. Similarly, when I moved to my current place, I decided not to have a TV in the living room, as it is a space for human interaction.

A good practice is to create a single association with a specific habit. Spending a lot of time watching television in the bedroom creates a strong association with the TV, making it more difficult to fall asleep. In fact, research suggests that people should only go to bed when they are tired, and if they cannot sleep, they must leave the bedroom. Over time, this establishes an association between the bed and sleep.

Temptations & Motivation

People can change their habits, but that doesn't mean they will forget about them. The key to success is discipline, and to make it easier, we should design our environment accordingly. That's why resisting temptation is challenging; once you know what reward you can get, you are likely to fall short.

If a cue triggers a habit, we can make it more visible and supercharged to make something happen. The greater the stimuli, the greater the effort applied.

Currently, the majority of available food is designed for contrast, such as popcorn that is salty and sweet simultaneously. This contrast keeps the eating experience novel, making it addictive. This is a supercharged stimulus.

Addictive things exaggerate something to increase desire (cue): pornography, beauty standards, constant likes that deliver more praise than we can get in a lifetime. This causes a dopamine spike in our brains.

A study conducted by neuroscientists James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954 revealed that by suppressing dopamine, rats lost the desire to be alive. They wouldn't eat or procreate; they didn't crave anything. In a few days, they all died. Dopamine is not only associated with pleasure but plays a fundamental role in motivation, learning, memory, and voluntary movement. When our brains predict that something will lead to a reward, there is a spike in dopamine.

Our brain's reward system is activated when we receive one or predict that we will receive a reward. So, anticipation can be as rewarding as the thing itself. That's why when our emotions are triggered, they win even when the logical explanation is way more reasonable.

Knowing that we are driven by reward, we can attach something we need to do to something we must do. I hate doing dishes, so I have a bad habit of accumulating a pile. To motivate me to clean it, I start listening to audiobooks while doing the dishes. Funny enough, I become more excited as the pile grows. Side note: after reading this book, I am making changes to not accumulate dishes.

Variable reward is the concept of providing rewards in a non-predictable order. Slot machines are the perfect example. Players know they could win the next time, but they might not. The unknown keeps them addicted to it. The variance in the reward creates the greatest spike in dopamine, making habit formation faster.

The habit stacking + temptation bundling formula is: After I [CURRENT HABIT], I will [HABIT I NEED]. After [HABIT I NEED], I will [HABIT I WANT]

Doesn't it sound like gamification?

When it comes to motivation, it is essential to work on tasks that prove to be a challenge. If they are too easy, you'll likely lose interest. If they are too difficult, you'll give up. When a task is challenging but just enough, that keeps you going. This is called the Goldilocks Rule.

Influences

Here's a captivating story from 1965 about Laszlo Polgar, a Hungarian man who applied his theory to nurture genius. He decided to teach chess to three sisters, immersing them completely in the world of chess. The children spent hours playing together, receiving constant compliments for their achievements. The environment was intentionally crafted to amplify anything related to chess. The culture fostered motivation and reward rather than force or coercion. As a result, Sofia, the middle child, became the world champion at the age of 14 and a grandmaster a few years later. Judith, the youngest, achieved grandmaster status at the age of 15, becoming the youngest grandmaster of all time. This incredible feat was only possible due to intentional and intrinsic habit design.

Beyond genetics, our identities are shaped by our environment and the people around us. Our habits are inherited from those in our proximity. The closer we are to someone, the more likely we are to imitate them. With this in mind, a powerful strategy is to surround yourself with individuals who embody the traits you aspire to possess. These individuals become living representations of the identity you wish to cultivate. This concept resonates with the idea of a "Scenius" from Show your Work:

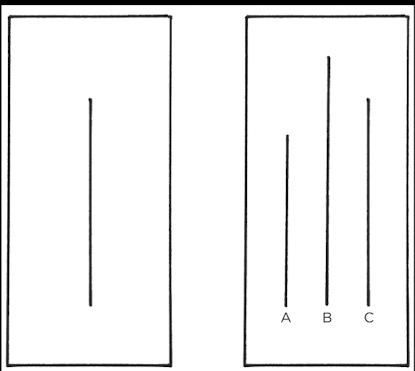

We are inherently designed to be part of a group. Studies conducted in the 1950s by psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated that people conform to lies due to peer pressure and self-doubt. In the study, participants were presented with a card displaying lines of different lengths and tasked with identifying the matching lines on another card. The majority intentionally chose the wrong line, and the greater the number of people making the incorrect choice, the higher the chance that a subject, unaware of the plot, would comply with the wrong answer. Nearly 75% of people went along with the incorrect choice.

Atomic Habits - James Clear - p. 118

When seeking something, we often check reviews done by others. We have a natural tendency to want to belong, even if it means being wrong. This reminds me of how seemingly normal and sane people get involved with cults, as explored in the documentary The Vow about NXIVM.

Regarding the people who influence us, they can be categorized into three groups:

- The Closest: Family and friends.

- The Mass: The collective "hive" of individuals like us.

- The Powerful: Celebrities, the wealthy, and influencers.

This behavior is deeply rooted historically, as more power often leads to increased opportunities. We naturally strive to be among the top and take actions to avoid lowering our status.

Craving

Behind our cravings lie fundamental, basic truths. Here are some of them:

- Conserve energy.

- Obtain food and water.

- Find love.

- Reproduction.

- Connection and belonging.

- Social acceptance.

- Reduce uncertainty.

- Achieve status and prestige.

- I would add shelter to this list.

- Minimum effort possible.

A smoker wasn't born with a desire to smoke, but the act of doing it reduces anxiety; it changes the current state. By recalling past events, the smoker predicts the best way to relieve anxiety. Habits, therefore, are solutions for current situations learned over time. The desire to change your current state is what motivates your actions.

Reframing

We can perceive things as half-empty or half-full. The moment we view something as a problem or a chore, it becomes just that.

The book shares an anecdote about someone asking a person in a wheelchair if it was difficult to be confined. The unexpected response was that the person felt free, not confined, because without the wheelchair, they would be bed-bound.

How can you change your vocabulary to see things from a new perspective?

How can you reframe your habits to highlight their benefits?

Action

Motivation is the key to adhering to a habit. To maximize a new habit, associate it with something you enjoy. Regardless of what you need to do, taking action is essential for change.

A noteworthy anecdote involves a photography class where the teacher divided students into two groups. Group 1 would be graded based on the quantity of pictures taken, while Group 2 would be assessed on the quality of a picture, even if it was just one. Surprisingly, Group 1 had numerous pictures, while Group 2 had none as they spent time debating what would constitute a perfect picture. A similar story is shared in Art & Fear, but in a pottery class.

The book introduces the concept of Motion and Action. Planning and studying are motions, but they don't generate results. If you're researching and reading references to write an article, that's motion. The article only comes into existence when you take action to write it. While motion provides direction, action makes the real difference. This resonates with the idea of focusing on the process rather than the goal.

Forming a habit requires repeated action. It's not about how long you do something; it's about how often you do it.

Taking action requires effort, and as humans, we naturally seek comfort and apply the least amount of effort possible—the Law of Least Effort. No one desires the habit itself; we want the benefits it delivers. Habits are methods to solve issues, and our aim is to have those issues resolved. Therefore, making things as easy as possible ensures you will follow through, even when motivation is lacking.

Neglecting to take action is detrimental in the long run. The secret is to consistently act even when motivation is low. Your identity should align, and the effort required should be easy and attractive to encourage action.

Rather than fighting difficulties, find ways around them. To make something easier, reduce the friction to take action. Designing your environment can significantly propel you into action. For example, if you want to drink more water, place water bottles in every room to minimize the effort of walking to the kitchen. Additionally, consider where you do things; find places close to your current routine. If the gym is conveniently located between your work and home, you're more likely to go.

On the other hand, increasing friction can make something harder to do. To stop watching TV, unplug it and have someone hide the remote. For an added challenge, remove the batteries and store them far away. Now, watching TV requires considerable effort.

Earlier, I mentioned making changes to my habit of cleaning dishes. Instead of accumulating piles, I now apply two strategies: clean each plate after eating, and practice Resetting the Room, a concept from Oswald Nuckols. Resetting the room involves returning the environment to its original configuration after each activity. This ensures that the space is always ready for use.

Habits function like links in a chain. Action X leads to action Y. To minimize effort, make your habits easy. Meditating for an hour may seem daunting, but starting with just one minute is much more manageable. The key is not to let the activity become an issue.

As a former trampoline athlete, one habit the coach instilled when learning a new skill was to stop when it was good enough for the day. The goal was not perfection, but consistent improvement without becoming burdensome.

This concept of reducing something to a bare minimum to make it easier is known as the Two-Minute Rule. The goal is to reinforce the identity we aspire to be.

Another strategy to increase difficulty is a Commitment Device. For example, if you want to gamble less, voluntarily add your name to the banned list. If you wish to reduce social media use, set a daily time limit. The harder it is to do something, the less likely you are to engage in it.

This journey may be challenging and monotonous, but success only comes through persistence. Keep taking action, even when it's hard; eventually, it will become easy. Embrace the boredom.

Small Victories

As mentioned at the beginning, the challenge with taking action in the realm of habits is that results often take time to materialize. This is referred to as a delayed-return environment. Many of our actions precede visible outcomes, and this has been the case for most of human existence. Only in the last 500 years, a mere blip in evolutionary terms, have we shifted to living our lives in a delayed-return environment. This shift presents a unique challenge. Behaviours such as smoking offer instant gratification while delaying the consequences. It becomes imperative to question whether the instant pleasure and rewards align with your long-term goals and identity.

Despite the inevitable need to ignore instant rewards in favor of delayed ones, it is beneficial to embed bits of immediate pleasure into the activities you need to do. For example, listening to an audiobook while doing the dishes can make the task more enjoyable. Conversely, introducing a bit of discomfort can aid in breaking unwanted habits.

To solidify a habit, one needs to experience a sense of progress or success. This feeling signifies that your efforts are paying off. An effective strategy involves incorporating visual indicators of progression. For instance, if your goal is to save money, open a savings account and designate it for something you desire, like a Leather Jacket; if you can name it as Leather Jacket. Each contribution visually reinforces progress and brings you closer to your goal—an immediate reinforcement.

Another engaging strategy is the paper clip method. Get two bowls. Fill one bowl with paper clips or small objects. Every positive step you take toward your habit earns you a move from one bowl to another. Witnessing more objects in the second bowl than the first provides a visually satisfying representation of your progress. If, for example, you need to make numerous work-related phone calls, track your progress one paper clip at a time.

Tracking

Research suggests that individuals who track their activities tend to be more successful in working toward their goals. Whether it's tracking weight, calories, or other metrics, being honest with yourself through tracking is crucial. We often hold distorted views about our own behaviour, and tracking provides several benefits:

- Obviousness: You have tangible evidence of changes.

- Attractiveness: You witness evidence of progress.

- Satisfaction: Seeing changes and progress feels good, fostering motivation to continue.

Tracking habits involves paying attention to the process, a fundamental aspect of habit formation. However, it's essential to note that tracking can create additional work, becoming a source of friction for some. Automating or simplifying tracking as much as possible increases the likelihood of consistent implementation.

It's crucial to emphasize that what we measure or track is what we aim to optimize. Choosing the right metrics is paramount, as the wrong measurement may reinforce undesired behavior. Measurement serves as a guide, providing insights to see the bigger picture rather than being the end goal itself.

Breaking the Habit

Everyone falls short and fails to do what they're supposed to at times. Missing a diet, leaving the dishes for tomorrow, or similar lapses are okay in moderation. However, when such deviations become the norm, addressing the issue becomes imperative. If possible, the principle of never missing something twice can be highly effective. For instance, if you skip the gym today, commit to not missing it tomorrow. Consider the perspective of a healthy and athletic person—what would they do?

The pain of missing a task often outweighs the actual effort of doing it. Understanding why it's detrimental to miss what you need to do is crucial for motivation:

The more immediate the punishment for an action, the higher the likelihood of avoiding it. A habit contract is a practical application of this idea. An anecdote illustrates this concept: Bryan Harris aimed to lose weight and created a habit contract with his wife and coach. If he failed to document his food consumption or weigh himself, he committed to dressing up every workday and Sunday for the quarter, in addition to giving $200 to his coach. They all signed the contract, and as conditions were later increased, he successfully achieved his weight loss goal.

Pick Your Battles

Our genetic code provides a predisposition that can either support or hinder us depending on the circumstances. Individuals excelling in various sports often possess both competence and a genetic predisposition for their activities. Take Michael Phelps, a highly successful swimmer with a physique well-suited for swimming due to relatively short legs and a long torso, making him less suited for running.

While genes influence areas where you might excel, they do not determine your destiny. The Big Five personality analysis—measuring openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—is scientifically relevant and can be tracked from birth. This analysis helps in understanding one's predispositions.

The key is to pick your battles wisely. Choosing activities aligned with your predispositions makes success more likely. To identify these predispositions, ask yourself:

What feels like fun for me, but work for others?

What makes me lose track of time?

Where do I get greater returns than the average person?

What comes naturally to me?

These questions can assist you in recognizing activities that are probably more suited to your natural abilities. However, for those that pose a challenge, proficiency can be achieved by embracing a unique approach.

Good Habits

Developing positive habits can significantly enhance your life over the long term. In the short term, the efficiency gained from spending less time and energy on trivial tasks allows you to allocate more resources to activities that truly matter.

However, it's crucial to avoid stagnation when cultivating good habits. Research indicates that once mastery is achieved, there is a slight decrease in performance. Therefore, it's important to keep challenging tasks alive to maintain continuous improvement.

Mastering a skill involves breaking it down and consistently improving each component until it becomes internalized. Regular analysis and reviews of your progress are essential, helping you remain aware and providing insights for further refinement.

The use of a Decision Journal is recommended to record important decisions, providing context for chosen courses of action and allowing for later reflection on their correctness.

Beliefs play a pivotal role in driving change, but it's important to note that allowing a singular belief to exclusively define your identity can act as a hindrance to adaptability. I once knew someone who wrestled with the idea of retirement for eight years, primarily because their profession had become intricately woven into their sense of self. It's crucial to be mindful of how you frame your beliefs. Choosing to identify solely as an athlete, for instance, can be more restrictive compared to embracing a broader identity—one that encompasses mental fortitude and a passion for overcoming physical challenges.

While acknowledging the benefits of habits, it's essential not to confine yourself to the constraints of outdated thought patterns and behaviours. Embrace the dynamism of personal growth and be open to evolving your mindset and actions beyond past routines.

The key to improvement lies in making small, sustainable enhancements, striving to be 1% better a thousand times.

Happiness manifests in the absence of desire. In the absence of longing, the impetus for change diminishes. The pursuit of achievement and pleasure centers around fulfillment and satisfaction, representing the very cravings we seek to transform. Often, our inclination is towards the pursuit of pleasure, a concept Lacan aptly refers to as the object of desire.

"He who has a why to live for can bear almost any how." - Friedrich Nietzsche

Curiosity surpasses intelligence, as being curious prompts action, and action leads to change. Emotions play a pivotal role in behaviour, with rationality following emotional responses. When suffering prompts a desire for change, and ignoring a desire leads to unsatisfied cravings, altering the craving itself is more effective than mere avoidance.

Attaining peace is contingent upon resisting the transformation of observations into problems. If there is no desire to act upon these observations, tranquility prevails.

When the reason is bigger than the obstacles, you will find a way.

In the pursuit of personal development, fostering curiosity holds greater merit than sheer intelligence. Curiosity compels action, serving as a catalyst for change.

Emotions, rather than logic, steer behavior. Damage to the emotional centers of the brain impedes action and, consequently, hinders the capacity for change. The interplay between System 1 (emotional responses and rapid judgments) and System 2 (rational analysis) underscores the dominance of feelings over logic. Convincing people through data necessitates an appeal to emotion.

Suffering serves as a catalyst for change, prompting individuals to address the sources of pain.

Neglecting a desire leads to unsatisfied cravings, contributing to our failure to resist them. The key lies not in ignoring but in transforming the cravings themselves.

The level of expectation directly influences one's satisfaction, with higher expectations correlating to increased pain.

Achieving satisfaction happens when liking something is bigger than how much you want it.

The impetus for change arises from the feeling that prompts action. Subsequently, the feeling of satisfaction perpetuates the repetition of positive behaviours.

Laws of Behaviour Change

Lets make break for a really funny passage:

Can you imagine asking your boss?

The Laws of behaviour changes are:

- 1st Law: Make it obvious (cue)

- 2nd Law: Make it attractive (craving)

- 3rd Law: Make it easy (response)

- 4th Law: Make it satisfying (reward)

Those same Laws can be inverted as:

- Inversion of 1st law: Make it invisible (cue)

- Inversion of 2nd law: Make it unattractive (craving)

- Inversion of 3rd law: Make it difficult (response)

- Inversion of 4th law: Make it unsatisfying (reward)

1st Law: Make it obvious

Anne Thorndike devised an ingenious solution to enhance the habits of visitors and staff at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, without directly requesting any changes or engaging in discussions with them.

They initiated a redesign of the cafeteria and conducted a six-month study. Water bottles were introduced to the existing refrigerators, and additionally, bottles of water were strategically placed next to all food stations in the room. Within three months, soda sales experienced a decline of 11.4%, while water sales witnessed a significant increase of 25.8%.

- Fill out the Habits Scorecard. Write down your current habits to become aware of them.

- Use implementation intentions: “I will [BEHAVIOR] at [TIME] in [LOCATION].”

- Use habit stacking: “After I [CURRENT HABIT], I will [NEW HABIT].”

- Design your environment. Make the cues of good habits obvious and visible.

2nd Law: Make it attractive

Ronan Byrne ingeniously applied his engineering expertise by modifying his stationary bike to interact with his laptop and television. His love for Netflix was intertwined with physical activity; he could only watch the streaming service if he maintained a specific cycling speed or faster. If he slowed down or reduced the speed, the show would automatically pause.

- Use temptation bundling. Pair an action you want to do with an action you need to do.

- Join a culture where your desired behavior is the normal behavior.

- Create a motivation ritual. Do something you enjoy immediately before a difficult habit.

3rd Law: Make it easy

The Japanese concept of Lean Production centers around minimizing various forms of waste in the production process. This is accomplished through the redesign of workspaces, production processes, and other elements. Workers no longer wasted time turning and twisting to reach their tools, leading to increased efficiency in Japanese factories and enhanced reliability of products compared to their American counterparts. A notable example is the contrast in service calls for American TVs, which were five times more common than Japanese TVs in 1974. Additionally, by 1979, American companies took three times longer to assemble their products compared to Japanese counterparts.

- Reduce friction. Decrease the number of steps between you and your good habits.

- Prime the environment. Prepare your environment to make future actions easier.

- Master the decisive moment. Optimize the small choices that deliver outsized impact.

- Use the Two-Minute Rule. Downscale your habits until they can be done in two minutes or less.

- Automate your habits. Invest in technology and onetime purchases that lock in future behavior.

4th Law: Make it satisfying

Since 1800, chewing gum has been commercially available; however, it only became a worldwide habit after 1891. Initially lacking any distinct taste, Wrigley revolutionized the market by adding flavors such as Spearmint and Juicy Fruit. They also began advertising chewing gum as a way to "Refresh Your Taste." The immediate reinforcement provided by the added flavor helped individuals adhere to this new habit, making Wrigley the most successful chewing gum company globally.

- Use reinforcement. Give yourself an immediate reward when you complete your habit.

- Make “doing nothing” enjoyable. When avoiding a bad habit, design a way to see the benefits.

- Use a habit tracker. Keep track of your habit streak and “don’t break the chain.”

- Never miss twice. When you forget to do a habit, make sure you get back on track immediately.

Inversion of 1st law: Make it invisible

If you wish to quit playing video games, once you've finished, unplug the console and store it away.

- Reduce exposure. Remove the cues of your bad habits from your environment. Inversion of the

Inversion of 2nd law: Make it unattractive

The book "Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking" is highly recommended for individuals seeking assistance in quitting smoking. It underscores the detrimental nature of smoking, portraying it as an unfavorable choice. By the conclusion of the book, readers arrive at the realization that smoking is not attractive at all. Here are some arguments extracted from the book:

- "You think you are quitting something, but you’re not quitting anything because cigarettes do nothing for you."

- "You think smoking is something you need to do to be social, but it’s not. You can be social without smoking at all."

- "You think smoking is about relieving stress, but it’s not. Smoking does not relieve your nerves, it destroys them."

- "You are losing nothing and you are making marvelous positive gains not only in health, energy and money but also in confidence, self-respect, freedom and, most important of all, in the length and quality of your future life."

- Reframe your mind-set. Highlight the benefits of avoiding your bad habits. Inversion of the

Inversion of 3rd law: Make it difficult

The author requests his assistant to change the passwords for all social media accounts every Monday. By Friday, she will provide him with the passwords, allowing him only the weekend to indulge in these platforms.

- Increase friction. Increase the number of steps between you and your bad habits.

- Use a commitment device. Restrict your future choices to the ones that benefit you. Inversion of the.

Inversion of 4th law: Make it unsatisfying

Roger Fisher, founder of the Harvard Negotiation Project, proposed an intriguing solution to the dilemma of granting access to nuclear codes to U.S. presidents. The potential consequences of launching a nuclear weapon may not feel "real" to the president, given the distance of thousands of kilometers. The process seems simple and detached. Fisher's solution involved implanting the codes in the chest of a volunteer, who would carry a butcher knife. If the president sought access to the codes, they would have to kill the volunteer to obtain them, making the potential death more palpable. This extreme measure aimed to deter hasty decisions and potentially save thousands of lives. Of course this proposal was never implemented.

- Get an accountability partner. Ask someone to watch your behaviour.

- Create a habit contract. Make the costs of your bad habits public and painful.